SF NIMBY's want to misuse historic preservation to block new housing. The board should beat them at their own game.

Shaking things up

I wasn’t able to get a recap for last week in time, although the three big pieces of local political news happened elsewhere this week. I’ll talk about them soon:

The Planning Commission voted 4-3 to advance Mayor Lurie’s family upzoning plan! It will advance to the board.

The story of St. Francis Wood

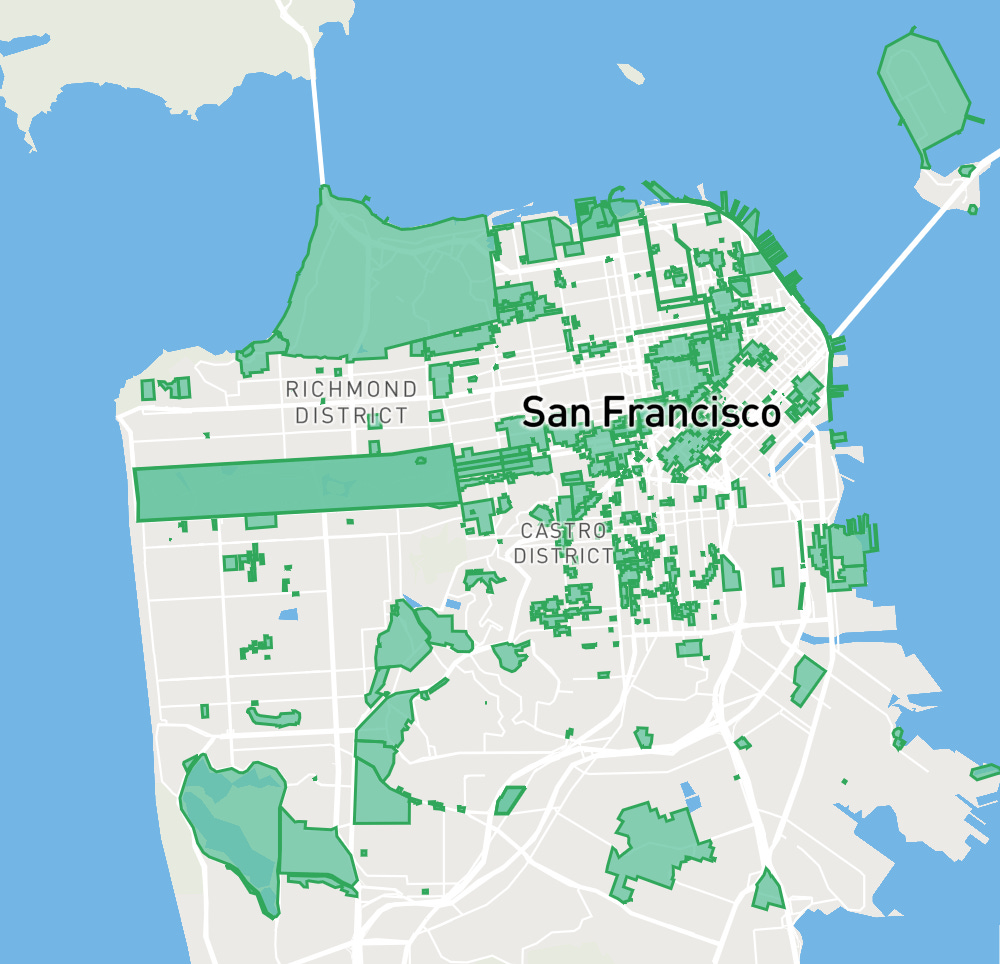

St. Francis Wood is a wealthy single-family neighborhood in western San Francisco, located just a couple of minutes' walk from the K Ingleside Muni line. Up until the latter half of the 20th century, it was also a white-only neighborhood, and today it flaunts little demographic diversity: 5% Hispanic and 0% black. In short, it is exactly the type of neighborhood that we should be trying to build more homes in. Yet local residents, hellbent on hoarding the privileges of their enclave, found a loophole to avoid this: historic preservation.

While there’s absolutely merit in preserving historically significant buildings or small slices of a city (for instance, the Painted Ladies), neighborhoods across the US have been abusing historic designations as a means of blocking new development for years–generally resulting in higher rents. St. Francis Wood was one such place; rather than protecting a handful of architecturally interesting buildings, they wanted it all saved.

After locals applied for a historic neighborhood designation in 2022, the San Francisco Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) promptly rubberstamped it with minimal fanfare. During the HPC’s hearing, the neighborhood’s racial history was of little note; it was mentioned in passing just twice. One of those times came from Commissioner Kate Black, who stated:

“Other than this really deplorable racial profiling and racial restrictions that occurred prior to 1980, this is an extraordinary district. It's a no-brainer to be a nomination. It meets the criteria. It's a very beautifully designed district…the best in the Bay Area.”

The applicants themselves were similarly tight-lipped in their application. Their general argument:

“Unlike many San Francisco neighborhoods that have undergone, and continue to undergo, tremendous physical changes, St. Francis Wood has remained true to its original plan and design and is one of San Francisco’s best-designed and most clearly realized example of a planned residence park.”

This approach ignores the fact that the planned residence park was designed like it was for the purposes of racial segregation, not in spite of it. These homeowners’ decision to preserve this design is therefore not a means of learning from some ugly history, but cementing it.

The formerly segregated district–the best in the Bay Area–was approved by the state.

What are we trying to preserve?

As Sacramento showers the state with a barrage of new laws to boost housing production, historic designations stand poised to become a go-to cudgel for local reactionaries. That’s because state law makes it more difficult to build new homes in these areas, largely by mandating environmental reviews and prohibiting certain streamlining options.

In San Francisco, we’ve already seen multiple abusive attempts to create historic districts rear their head this year. Most notably, the State Historical Resources Commission will consider whether to list North Beach on the state registry sometime in the near future. This comes after our HPC endorsed it earlier this year. But residents’ attempts to shield themselves from Sacramento’s reforms extend far beyond the tourist district and into the decrepit and capped housing stock throughout the neighborhood. Despite originating as a working-class neighborhood, North Beach’s refusal to build much of any new housing for decades helped ensure it became just about as gentrified as anywhere else in the Bay.

Facing a housing crisis of unprecedented magnitude, San Francisco political leaders cannot continue to stand idly by and let this abuse happen. In a city that has seen its rents grow without end while our streets fill with trash and tents, what is it really that we’re seeking to preserve?

How the Board can fight back against state designations

There are two basic avenues for creating a historic district in SF:

Through the state/national historic register (there are around 40 such districts in SF).

Through the local city process (there are around 20 of these).

While the former makes it somewhat more difficult to build housing, the latter can be brutally restrictive. Thankfully, the state route is more common because it’s politically simpler and offers stronger financial incentives (in addition to being less strict).

Unfortunately, the non-city process is more difficult to reform at the board level. Much of it is under the state’s purview (bad enough), but even worse, we’ve put the rabidly anti-housing HPC (an unelected body of historic preservation nerds) in charge of submitting a recommendation on any potential district to the state. The State Historical Resources Commission (SHRC) then rules on it, before it heads for national review. Unsurprisingly, the HPC unanimously endorsed the creation of the district. And because the HPC is charter-empowered, the board can’t really touch it. Yet there’s room to maneuver.

Back in January, Mayor Lurie requested that the SHRC delay a hearing on the North Beach application, to which they relented. They have still not held a hearing half a year later, and will not do so this year. There’s nothing in our charter or state law that says Lurie can officially ask for a delay, but he used the bully pulpit to do so anyway. And herein lies a potential answer: while the HPC is tasked with providing San Francisco’s “official” recommendation under the Certified Local Government Program (with the help of the Planning Department), it’s fundamentally ill-suited to weigh historical merit against the necessity of building new homes. In their eyes, every SF building built by a segregationist a century ago is a sacred relic; every new development is the desecration of our history. The fact that the city might grow or change by necessity is not just inconsequential but antithetical to an incontrovertible truth: God created time and San Francisco in an instant at the turn of the 20th century.

San Francisco’s more responsible bodies should be able to express concerns or offer competing recommendations against the HPC.

Whether or not these recommendations are “official” is irrelevant, as we’ve seen with Lurie’s request. NIMBYs have long understood this when it comes to blocking housing; even if laws on the books don’t ban an apartment, political pressure can nevertheless force a developer to cave. The goal is noise and obstruction. That said, the Mayor can’t be put in a politically untenable position where he’s going against every historic district that comes up. Instead, city leaders could consider a couple of routes.

The board or the Mayor should create something like a housing equity force that would review and give its own comments on (among other exclusionary NIMBY actions) potential historic districts. This group could act as a shadow HPC, with the specific purpose of promoting housing affordability or with the goal of combating exclusionary housing practices. Relative to the other suggestions in this article, this reform seems the least politically costly. While Lurie tapped a “housing and economic development” czar to lead a new office, it lacks separation from him.

The board could move to hold regular hearings on historic applications and offer non-binding resolutions in support or in opposition. In essence, the strategy should be to find competing voices against the HPC through any means necessary. This would likely send a stronger message than an advisory committee, although it would be more politically costly and difficult to mandate in the same way.

While not my idea, the Planning Commission could be made to perform an analysis to ensure that a potential district isn’t undermining SF’s legal responsibility to affirmatively further fair housing. Legislation passed last year at the state level requires cities to do something to this extent in an annual report given to the state, but it does not tie this report to each individual historic district designation.

This is also a system that could work to address past abuses like St. Francis Wood. If every five or ten years the board or an equity force reviewed existing districts, it would create targeted periods to fight back against the failed polices of our recent history. And even if repealing those districts wasn’t in the cards (it is legally possible, though), this approach could dissuade new neighborhoods from abusing the process and finding their history and their intentions regularly highlighted.

On that note, maybe the board could even find other creative ways to highlight that history. According to state law, certified local governments have a legal ability to pursue educational outreach, and the SF code lists that the HPC and the Planning Department may “disseminate information to the public concerning those structures, sites and areas deemed worthy of preservation.” St. Francis Wood’s legacy of segregation and exclusionary zoning seems like information worth disseminating; quaint neighborhoods might be more hesitant to become preserved districts if a sign were added on every block highlighting the racial history hiding behind that beautiful architecture.

How the Board can prevent local designation abuses

Whether the North Beach activists are successful at the state level, they could choose to pursue the local process. And so might other neighborhoods, particularly as Sacramento pushes more and more reforms. These “Article 10 Districts” could be a viable cudgel for SF residents displeased with their imminent upzoning.

Much of our local historic preservation process is inscribed in 2008’s Proposition J, which created the HPC. Since the 2008 Proposition, the board had never introduced a local historic district (as far as I can tell from Legistar) until President Mandelman successfully passed two small ones earlier this year after residents voiced their support: Alert Alley Early Residential Historic District and Chula-Abbey Early Residential Historic District.

Whether this could be the beginning of a trend is difficult to say; at the moment, the state register process is much easier, and there have been few Article 10 Districts created in the past decade. That said, it’s worth being prepared for, and the types of reforms I suggest lower down utilize approaches that would be transferable to other housing reforms.

That said, there are limitations to what the board has the power to do on this issue. Because a proposition created the HPC, any reform that went against the letter or intent of that legislation would need to be okayed by an update to the Charter (the city’s constitution), which would require voter approval; that’s not viable.

This means certain things are set in stone: the HPC has the power to recommend approval of districts, and they then send it to Planning. Planning has 45 days to comment (but cannot block the designation) after which point it goes to the board to finally decide the matter. While the current board is unlikely to approve grotesque abuses, the balance of power could turn on a dime. Even now, pro-housing supervisors may feel pressure to support historic designations within their district.

But there are viable reform options. In fact, anti-urbanist Supervisor Aaron Peskin passed an ordinance in 2012 aimed at codifying easier pathways to designation status. Pro-housing supporters should fight back by using the longstanding NIMBY strategy: add bureaucratic hurdles and increase community review requirements for new historic districts—especially reviews tied to social justice goals. Below, I’ve listed some plausible ideas, although this is admittedly an extremely complex legal issue; any supervisor interested in reform would want to start by winding back the 2012 ordinance.

Make it more difficult to apply for historic designation:

Peskin’s ordinance mandated that the HPC must hold a hearing to consider a historic district designation if the majority of the property owners in that district show their support. That’s an extreme level of veto power for a tiny minority, and it clearly advantages wealthier residents. Instead, the board could require signatures from a supermajority of property owners, or even require that the signatures arrive within a tight timeframe; in high-resource areas, this number could be increased. They could require this for board and HPC-initiated processes as well.

The fee to submit a historic district application in SF is just $1,651 plus administrative costs if Planning feels like it (they “may waive time and material charges for the designation of a Historical District to encourage Citywide preservation activities” according to the code). In contrast, even in Los Angeles—a city famous for its opposition to new homes—the creation of a historic preservation overlay zone costs over $140,000. We should address this.

Don’t ignore the optics:

If this process is truly about preserving history, district applicants should have to extensively detail their district’s history of segregation and the legacy born of that history. Planning, as I suggested in the previous section (again, not my idea), should likewise analyze whether this new district would affirmatively further fair housing as required by state law.

Wealthy residents support segregation without ever having to face the people they're trying to wall out. That shouldn’t be the case. The board should require outreach by high-resource neighborhoods to priority equity neighborhoods during the application process—ensuring these neighborhoods aren’t doing something strongly opposed by less affluent residents. Hell, make the high-resource neighborhood pay for the costs of this process as well. At a minimum, if this isn’t possible, the board should ensure the city is reaching out to priority equity neighborhoods when any historic district is on the table.

Look toward the future:

If a historic district application fails, no matter: thanks to Peskin’s legislation, they can just apply again in a year. The board should remedy this potential for repeated abuse, requiring a five or even 10-year gap between applications.

Times change, needs change, priorities change. So when a historic district is created, that shouldn’t be the end of the story. Instead, the board should consider legislation to mandate reconsideration of existing districts every X number of years.

Whether the board works with the City Attorney’s office to make any of these specific reforms viable, they have an obligation to act. And on every housing issue where it’s viable, pro-housing legislators need to be more willing to beat NIMBYs at their own game.